By Michael Brownbridge

What Can You Do to Ease the Transition to a More Biologically Based Approach to Pest and Disease Management?

What do we mean by "biologicals"? This is a catch-all phrase for biological pesticides (biopesticides—includes biochemical and microbial products) and macro-biological control agents (BCAs— insect and mite predators, and parasitoids)

"I've used chemicals to control pests and diseases throughout my career, but I get the sense they're not working as well as they used to and I'm tired of suiting up at the end of the day to spray. My workers don't like it either. What do I need to do so that I can start using biologicals? I may not want to give up chemistry entirely—is that possible? And I want to start next year."—A. Grower

This type of request is not uncommon. It's easy to provide a response that focuses on the mechanics of using biologicals, while glossing over the groundwork that needs to be done to prepare for and facilitate the transition. While this piece may not uncover anything radically different from what's already out there, it's my hope that it may provide a checklist of sorts to make the journey less stressful and more successful. The starting point is this: What should a greenhouse owner or manager and a production team do now to prepare for a move to biological control in 2026 and beyond?

One immediate step is to review current chemical usage. This has two purposes: First, have a target list of materials and know what each was being used for. The goal is to replace as many of these with biologicals, so this list will allow you to see what biological alternatives there are.

Second, to immediately remove some of these materials from your current year's program. Some chemicals have long residual activity (like Avid and Abermectin) and can impact biocontrol agents months after their use. Transitioning to a "low residue" program a year ahead of time makes the greenhouse a more welcoming place for natural enemies.

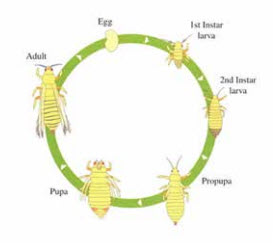

LIFE CYCLE OF WESTERN FLOWER THRIPS.

Several biocontrol agents can be used to manage different life stages of this pest:

- Eggs—Laid in the leaf tissue, some control by dipping in oil products like SuffOil-X

- First instar—Young larvae controlled by predatory mites such as Neoseiulus cucumeris

- Second instar—Older, larger larvae consumed by Orius spp. and entomopathogenic fungi such as Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium brunneum

- Both the pro-pupal and pupal stages are soil-dwelling and can be managed using entomopathogenic nematodes such as Steinernema feltiae and predators such as Stratiolaelaps scimitus (Hypoaspis) and Dalotia coriaria (Atheta)

- Adults—Entomopathogenic fungi

Figure credits: Skinner, M., B.L. Parker and J.S. Kim. 2014. Role of entomopathogenic fungi in integrated pest management, In Dharam P. Abrol (ed.) Integrated Pest Management: Current Concepts and Ecological Perspective, pp. 161-191. Academic Press.

WHY SHOULD YOU CONSIDER USING BIOLOGICALS?

WHY SHOULD YOU CONSIDER USING BIOLOGICALS?

Resistance. Key pests (like thrips, spider mites and whiteflies) and diseases (including Botrytis, Fusarium and powdery mildew) have evolved resistance to multiple active ingredients. Use of biologicals in an integrated plant health management (IPHM) program helps preserve the active lifetime of synthetics that still work. That list is getting shorter and replacements don't come along very often.

Safety. Biologicals are safer for workers and our environment, and in the case of BCAs, there are no re-entry intervals (REIs) to worry about. Most biopesticides have REIs of four hours or less, making it easier to incorporate their use into a production program without disrupting other crop-management activities. Generally speaking (although there are exceptions), they're also softer on natural enemies.

Sustainability. Greater integration of biologicals into an IPHM program helps reduce chemical inputs, contributing to sustainability goals and (for many

producers) allows businesses to conform to sustainability guidelines issued by some of the major retailers around products that can or cannot be used, as well as acceptable residue levels on plants or vegetables.

DISPELLING SOME MYTHS. While biological products are increasingly used successfully in multiple indoor crops, adoption is still hampered by perceptions that they don't perform as well as conventional pesticides, that they're too complicated to use, and are unreliable, expensive and can only be used in organic systems.

Let's take a moment to dispel these myths. Used correctly, BCAs and biopesticides are highly effective and will deliver consistent results. Today's products and formulations are significantly better than those of even 10 years ago, making them easier to use in both organic and conventional systems, so it's not an either/or choice.

And let's put a stake in the heart of the statement, "You can't use biologicals with chemistry" once and for all. Biopesticides are compatible with many synthetic products, but it's essential to confirm their physical and biological compatibility before tank mixing or using together in a rotation. Chemical pesticides are typically more disruptive to BCAs, but some products are considered "softer" on beneficials and can be used to support a biocontrol program with minimal negative impact. Treatments can also be separated in time and space to avoid direct contact with the BCAs—applying a systemic insecticide by drenching rather than as a foliar spray, for example, avoids direct contact with beneficial species. We can continue to have pesticides in our back pocket if we need to use them, but biology allows us to maintain their efficacy so we can continue to use them effectively if needed.

And is it really more expensive? We're not advocating using biologicals as well as the same chemical inputs, but replacing chemistry with biology. Initially, costs—if you do a product-toproduct comparison—may be higher, but over time and with experience, costs inevitably come down and there are frequently other cost savings that accompany biological programs. Aside from the products, consider those costs associated with applying synthetics: equipment, equipment maintenance, time spent applying materials, having to shut down a greenhouse during the application and REI period, the additional labor expense of having a qualified applicator spray the crop, etc.

Furthermore, biological materials provide extended protection to a crop, which can further reduce labor costs or free up labor for other tasks. When you factor in all associated costs and the savings that can be realized, the argument can be made that using biocontrols can be a more economical proposition to the business. And, unlike chemistry, microbials can deliver many other crop benefits. Use opportunities lie in positioning biopesticides and BCAs in programs that support their success and allow us to get the most from the strengths and versatility that they can bring.

PLANNING TO MAKE THE MOVE

PLANNING TO MAKE THE MOVE

- Mindset and commitment are key. To quote well-respected biological control expert Ron Valentin, "It's a mindset change. We need to stop thinking about biological control as a product you buy and instead see it as a system you cultivate."Use of biologicals requires proactive action, preventing pest and disease problems versus the curative, reactive mindset we're used to when using chemistry. Taking action before you see a problem? Yes, that's the first hurdle. Many so-called failures are due to poor timing and improper application—using biologicals when there's nothing left in the chemical cabinet. Not the ideal time to use them.

Think proactively. This is where crop records can be extremely useful, as they provide insights into the what, when and where. What disease and pest issues have you dealt with in the past? When did they occur and in which crop(s)? The most successful bio programs start in propagation and there are several tools and strategies that have been proven to be critical to the season-long success of such programs. If growing a spring crop from vegetative cuttings, for example, consider the value of dipping those cuttings before sticking as a means of eliminating hitchhiking pests or promoting early root growth.

Commit. Becoming proficient in biocontrol is like learning any new skill. If you want to do it well, you have to be willing to invest your time and resources and that of any other dedicated staff. Ask the question up front: Do you have knowledgeable people with the right skill sets on staff to take this on? Having one person dedicated to the initiative— to manage, coordinate and take ownership of it—creates accountability, focus and avoids duplication. Empower and support them, but don't neglect the rest of your staff. They're additional eyes that can monitor the health of the crop and ensure that crop-management decisions don't negatively impact the efficacy of the biologicals. Doing the job right necessitates time spent monitoring

the crop to keep ahead of pest and disease problems, to ensure strategies are working, and to adjust as needed. Make sure that the person dedicated

to this task isn't reassigned to assist in other areas of the greenhouse when things get busy. - Rome wasn't built in a day. You won't build the Colosseum on your first attempt. Build experience and confidence across your team first. Start

small. Don't try to implement a program in a crop that faces multiple production challenges every year. Chose a crop you know well and biological strategies that have a track record of success.Let's say western flower thrips are a recurrent problem on a crop that otherwise performs well. There are

several complementary biological tools with documented "foolproof" methods associated with their use that can be considered in this case. Nematodes,

for example, are often considered a "gateway biological," as they're easy to use and apply, and work well against soil-dwelling stages of western flower

and other thrips species. They have a long history of successful use in affected crops, so you don't need to reinvent the proverbial wheel. (More on

this example later…)Rather than going into a full bio program, consider incorporating a bioinsecticide or biofungicide into a spray or drench rotation as the first step on a biocontrol journey. Biopesticides are a good way to ease into a bioprogram, as the methods used to apply them are very similar to those employed for conventional pesticides. Biofungicides can be inserted into a fungicide resistance management program, replacing one or more chemical applications in that rotation. There are now many working examples of hybrid programs that work as well as (or better than) all-chemistry rotations and you get double the benefits— chemical inputs are reduced and the likelihood that diseases will develop resistance are diminished.

- Do your homework and educate the team. Based on the target crop, do you and your team know what pest or disease issues you may have to deal

with? Do you know when these occur, what they look like and what plant symptoms are indicative of an infection or infestation? Do they happen in the

same crop and location year after year? This is when crop scouting records are invaluable, as they help define what your target crop will be, the pest(s) and disease(s) you're likely to encounter, and the biological options that are available. With this information, start to do your research to understand how the different biologicals work, the life stages of the pest they work against or times when they can be used to prevent disease and how they're best deployed. Let's go back to the earlier example of managing western flower thrips: The life cycle and biology of thrips differ from species to species and the controls you select must be appropriate. Western flower thrips lay their eggs in plant tissue; first and second stage larvae are motile, feeding on the

foliage and flowers, whereas pre-pupal and pupal stages are non-feeding stages in the soil. Adults feed on the foliage and flowers. Some biocontrol

agents work on larvae, others on the pupal stages or adults. In a basic program, you could consider three complementary biologicals: predatory

mites, like Neoseiulus cucumeris, which consume young thrips larvae on the foliage. Or combine their use with sprays of entomopathogenic fungi,

which infect larvae and adults, and entomopathogenic nematodes for the soil-dwelling stages, and you have a program. Integration of different natural

enemies to target all accessible life stages of the pest is inherently more effective and reliable.Knowing which biologicals you can use is one thing, but it's equally important to understand when and how to use them. When is the best time to make a first release (early), a biofungicide treatment (propagation) or bioinsecticide application (early)? Which method of application should be used—for

example, predatory mite sachets versus sprinkling a bran formulation over the crop? Does your choice remain static through the life of the crop or are some natural enemies better suited to cool or warm conditions? When should biofungicides be used and what's the best formulation to use based on your business infrastructure and capabilities, such as pre-incorporating a granular formulation into the growing medium versus the use of a biofungicide drench? Are there any other strategies that can enhance a program (I already mentioned dipping to mitigate incoming pests on cuttings)? What other pest control products can be safely used with them and what cannot?There are many resources available just a click away on manufacturers' websites or university extension sites. Ask your peers, some of whom may be seasoned practitioners. Consider retaining the services of a crop consultant or independent scouting service. This can take the load off employees and

provide essential crop data (including a record of how well your biologicals are working) on a regular basis. Attend webinars, local or national meetings and ask questions. Read and learn and bring the team along with you. A dedicated and well-educated team will be more attentive to detail if responsibilities and information are shared. Communication of the goals and content of the program across the team and the entire staff will also help prevent mistakes. How many times has a pesticide been applied by mistake in an area where biocontrol agents were being used?

Source: https://www.growertalks.com/pdf/BioSolutions_Guide_2025.pdf